Late Thursday afternoon I park in the lot alongside Our Lady Queen of the Angels Church, whose overwrought colonial name is La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Angeles de Porciúncula, and which those of us on intimate terms with the place thankfully refer to as just La Placita. Every visit here brings me intense waves of nostalgia.

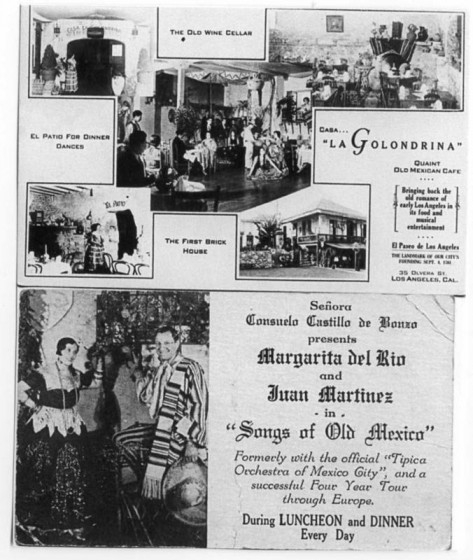

I was baptized here, as was my father before me. My grandparents worked across the street at La Golondrina restaurant on Calle Olvera. Since I was a kid I have been savoring the #2 plate at La Luz del Día (two carnitas tacos rolled in hand-made tortillas, rice & beans); my parents, during their courtship and through their 51 years of marriage have indulged the grease-dripping taquitos at Cielito Lindo. I covered dozens of press conferences at the church during the liberation theology-influenced tenure of Fr. Luis Olivares in the 1980s, which I chronicle in my first book, The Other Side. Every December I bring my daughters to the kiosk in the plaza across from the church to visit the larger-than-lifesize Nativity scene. A few weeks ago I stood on that stage and co-emceed an event welcoming Mexican poet and peace activist Javier Sicilia and several dozen other “víctimas” of the drug war as their caravan passed through Los Angeles en route to Washington, D.C.

La Placita and Olvera Street, site of the Spanish pueblo’s founding in 1781, don’t add up to much in terms of architectural style or scale. But the place is powerfully haunted by political spirits—one of whom is making a grand re-apparition.

On Tuesday Oct. 9, Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros’ L.A. masterpiece, América Tropical, will officially be re-revealed to the world, eighty years to the day after its original appearance. I tell the story of its unveiling and subsequent censorship by whitewashing here.

I tour the newly-completed América Tropical Interpretive Center in the Sepúlveda House on Olvera Street alongside many artists and activists who agitated and organized over decades—decades!—for this moment. Among the cohort: Luis Garza, Carol Jacques, Leo Limón, Rupert García and Dr. Irene Herner, Mexico’s foremost Siqueiros scholar. Barbara Carrasco is there too, beaming in front of the tribute to Siqueiros that she painted with John Valadez and a team of young talent. Present in spectral form is the late Dr. Shifra Goldman, one of the foremost critics of her generation to focus on Chicano and Latin American political art and whose early gaze upon the mural made the art world take note. Jesús Treviño, a foundational Chicano filmmaker wasn’t in attendance but he too was among the pioneers who promoted of the idea of rescuing the mural, contributing a documentary that in itself was an integral part of the restoration process.

As at many opening receptions, I’m too distracted by the social buzz (“¡Quibole! ¿Cómo estás? Haven’t seen you in ages!”) to get enough of a critical sense of the exhibit, which was curated by the Getty Conservation Institute. There are interactive touch-screen timelines, what appears to be a good general staging of the political and historical context within which the mural was originally presented, and what at first glance looks like an inadvertently kitschy simulacrum of the scaffolding and paint buckets that Siqueiros worked with upstairs eight decades ago. I cringe when I see my own face on one of the touch screens, speaking to the viewer from my office at LMU. (The irony of holding academic authority in middle age is not lost on the consciousness of my inner twenty-something, the anti-academic idealism that I fist-pumped as a young man.)

And now it’s time to go upstairs and view the mural itself. I have only seen black and white photographs of it for the last twenty-five years. But I’ve been talking about it, in classrooms and at dinner parties and with my own family for a long, long time. This is not just a crucial representation of the city’s history of ethnic and class and artistic conflict. This is also very personal. This is my grandparents playing corridos and rancheras at La Golondrina for the tourists that booster Christine Sterling gathered for her ethnic theme park in the 1930s—at exactly the same time that Siqueiros is upstairs on the roof, furiously painting against the folkloric essentialism that he believes the early creative impulse of the Mexican Revolution has devolved into. This is the one degree of separation between my family’s unbroken history across four generations in this city, and the deportations of hundreds of thousands of our paisanos. (One of the first raids of the Great Repatriation occurred in La Placita just months before Siqueiros painted the mural—an event that powerfully informed its content.) This is holy water dribbling over my head in 1962. This is me dreaming of another revolution, as I sit in the pews of La Placita two generations after Siqueiros, listening to Fr. Olivares stirring sermons that shaped the gospels into real-world parables with real-world implications and political challenges.

This is me yearning for history. I was obsessed with the idea in my twenties: “I must have a history,” I wrote, because I was raised in the past-less paradise, the city of the future that shunned the past except in distorted renditions projected by Hollywood that reflected all the country’s stereotypes and justifications for one conquest after another (call it the Mexican-American War, call it the Zoot Suit Riots, call it the LAPD, call it urban renewal, call it gentrification, call it Eli Broad and Frank Gehry).

Carol Jacques and Dalila Sotelo of the Amigos de Siqueiros non-profit organziation that will ultimately run the visitor center, tenacious organizers both of them, escort me into the elevator. The doors close. It has new-car smell, I joke. And then we go nowhere—the elevator does not seem to want to deliver us to the rooftop. A glitch that’ll have to be fixed by the time mayor Antonio Villaraigosa (who played no small role in the project, helping appropriate millions of dollars for its development) and all the other dignitaries arrive on Tuesday. We take the stairs.

It is late afternoon and the autumn sun catches the mural with a soft yellow tinged with amber. I am shocked at the level of color and detail that bleed through what remains of the whitewash. (Long ago, conservators determined it would be impossible to fully restore the mural because the whitewash had embedded itself too deeply into the mural’s original paint.) The sinewy branches of the tropical trees that frame the Maya temple and stelae stand for the power of history itself—the representation of memory wielded in this case to rewrite imperial history from below.

And now I focus my eyes on the figure that ensured the mural’s erasure: the indigenous man crucified on a double cross, an imperial eagle—an undeniable reference to United States policy toward Latin America—bearing down upon him.

1932: the Great Depression and the Great Repatriation.

2012: the Great Recession, Arizona’s SB 1070 and the Obama Administration’s disgraceful record number of deportations.

It is 1932 and 2012 at once: before us, in its ghostly-almost-material state, the mural is simultaneously revealed, whitewashed and re-revealed in an endless cycle.

It is the story of my city and it is my story. With every word I write, I try to re-reveal myself to myself and to the world that would deny the complexity of the history that brought me into it.

4 Responses to América Tropical: Re-revealing Siqueiros’ L.A. Masterpiece