The re-unveiling of the Siqueiros mural will push Los Angeles to engage its past.

Los Angeles Times, September 19, 2010

Seventy-eight years ago, on Oct. 8, 1932, David Alfaro Siqueiros — at the age of 36 already an important Mexican artist but not yet the icon he would become — sweated shirtless on a cool fall night as he “painted for dear life,” The Times’ art critic, Arthur Millier, wrote at the time.

He was on a deadline, and running late. The unveiling of the work “America Tropical” was just hours away, and the very center of the mural had yet to be filled in.

So far the elements of the mural included a Maya pyramid, the sinewy and winding branches of jungle trees, and an eagle hovering with open talons. On his final night of work Siqueiros added an indigenous man crucified on a double cross, with the eagle — now undeniably an overt reference to American imperialism — bearing down on him.

At the unveiling ceremony, which was attended by hundreds, the spectators gasped, according to Millier. Some because of the aesthetic power of the work, others at its political audacity, which doomed it. Within a few years, “America Tropical” was whitewashed and for decades largely forgotten.

What was hidden by ideology, paint and neglect is slowly reappearing. Last week a groundbreaking ceremony was held for the Siqueiros visitor center, which will provide a vantage point from which to see what remains of the mural, along with exhibits on the artwork and the artist’s stay in Los Angeles.

The timing of “America Tropical’s” reemergence in the midst of a nativist reaction means it can rejoin a debate it originally commented on. In 1931, just before Siqueiros’ arrival, Depression-era anti-immigrant sentiment boiled over and the “repatriation” of hundreds of thousands of Mexican laborers (and in many cases U.S. citizens of Mexican descent) began locally with a raid at the Old Plaza.

During his stay in Los Angeles, Siqueiros, a lifelong revolutionary, absorbed the political moment. He painted on behalf of indigenous Mexicans, then as now among the most oppressed and rebellious of Latin America’s peoples — and, by extension, Mexicans in America, then as now a disposable labor force that doubles as scapegoat in troubled economic times.

The commission came from F.K. Ferenz, director of the Plaza Art Center gallery, housed in the Italian Hall, but the ultimate approval came from Olvera Street’s main booster and renovator, Christine Sterling. My family played a modest role in the story.

My Mexican grandparents, Juan Martínez and Margarita del Río, strummed guitars and sang the corridos and rancheras of the day, billing themselves as “Martínez-del Río, los famosos cancioneros mexicanos.” There was plenty of work for Martínez-del Río, performing for two distinct audiences in L.A. — Mexicans nostalgic for home and white Americans captivated by “Old Mexico.”

In 1932, they were hired by Consuelo de Bonzo, a restaurateur Sterling invited to open an eatery on Olvera Street. While Siqueiros was on the rooftop painting provocation, my grandparents were downstairs at La Golondrina Restaurant (run today by Vivien Bonzo, Consuelo’s granddaughter), playing for the tourists, and at the same time prying open the door of my family’s American dream.

When a flowery “America Tropical” theme was suggested to Siqueiros — perhaps at Sterling’s urging — Siqueiros sensed an opportunity. “It has been asked that I paint something related to tropical America, possibly thinking that this new theme would give no margin to create a work of revolutionary character,” he said at the time. “On the contrary, it seems to [me] that there couldn’t be a better theme to use.”

In the immediate battle between Sterling and Siqueiros, Sterling had the upper hand. She was the grande dame of Olvera Street, after all, who had rallied the city’s political and business elites to build the “Old Mexico” she imagined. She deemed the mural anti-American, justifying the whitewashing.

But Sterling lost the war. In the last generation, much of L.A.’s hidden history has begun to resurface. Parts of “la zanja madre,” the city’s original main water ditch, have been uncovered near downtown. We have begun to imagine what the L.A. River was like before it was trapped in concrete (and what it could be again one day). Musicians and theater artists have conjured the barrios of Chavez Ravine before the Dodgers came to town. And generations of Chicano and Chicana artists have continued Siqueiros’ legacy of public art, often invoking “forgotten” chapters of local history. Indeed, it was the pioneering generation of Chicano artists who initially brought attention to “America Tropical”.

Early efforts to save “America Tropical” stalled more than once. It is no coincidence that the construction of the visitor center, the final step before the mural can be unveiled again, has finally gotten underway during the administration of the first mayor of Mexican descent — and one with an activist background — since the 1870s.

Ironically, the mural was beginning to reveal itself even before the campaign to save it began in earnest. Time, the elements and decades of L.A. smog helped expose enough of the artwork for the outlines of its dramatic figures to emerge in ghostly fashion from the chalky surface.

The centerpiece of the visitor center, which will be run by the nonprofit Amigos de Siqueiros, will be a viewing platform on the roof of Sepulveda House, next to Italian Hall, and a protective awning over the mural. There is also a plan for a digital projection that would infuse “America Tropical” with its original colors (or at least an approximation, since at the time of the whitewashing color photography was still not widely available). Imagine standing before the vast wall — 18 feet high and 82 feet wide — and watching it morph from its ghost state into the furious color we know Siqueiros used. Then the color would bleed away, in a cycle mimicking the creation, whitewashing and reemergence of the mural. It would also symbolize the city’s troubled relationship with its own past.

Re-revealing Siqueiros is reminiscent of other places that have attempted to unearth history. Chile, El Salvador and South Africa have had their truth commissions and built monuments to what and who was “disappeared.” “America Tropical” is on a much more modest scale, of course, but in the end this is about more than a painting on a wall. It’s about the “city of the future” finally engaging its past.

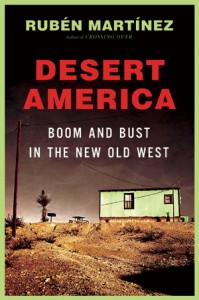

Rubén Martínez is an English professor at Loyola Marymount University. He is finishing a book about the desert West and borderlands for Metropolitan Books.