The riots needed their narrators, and this bilingual son of immigrants embraced the role. Until he didn’t

(Los Angeles Magazine, 4/1/2012)

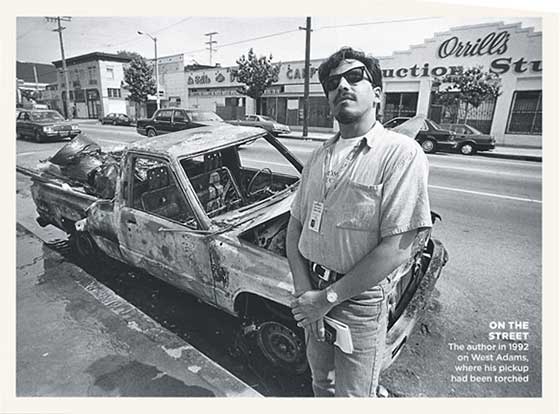

Photograph by Ted Soqui

On April 29, 1992, I was 29 years old and a reporter at the L.A. Weekly. I had a modest following among the city’s progressives, particularly those sympathetic to immigrants’ rights. Forty-eight hours later I was riding limousines to TV studios, had a worldwide audience and, soon enough, invitations to lecture. Voices on the phone had all kinds of propositions for work. I became a bona fide spokesperson for “my people,” who had, to the shock of many, been central protagonists of the violence. (In an oft-cited riot statistic, ultimately more Latinos were arrested than African Americans.)

I was perfectly positioned for the role. I was bilingual, the son and grandson of immigrants. I also had, I’m now thoroughly embarrassed to admit, the right look of the moment. Borrowing from the Gipsy Kings and various incarnations of Latin pop, I wore a goatee, my hair in a ponytail, red shirts, and flamboyant ties. Sleeplessly bounding from KCET’s studios, where I had just started cohosting a local politics and culture series called Life & Times, to barrios in flames to my desk at the Weekly to emergency activist meetings, I didn’t have much time to reflect on that positioning, though in retrospect the angry young man I embodied was fueled in great part by the tension inherent in the role. The promise of the civil rights movement had been to arrive at a place where we were no longer judged by the color of our skin, but the “white” media needed me to be brown.

Which I was. And of course I was so much more. I was middle class and a generation removed from Latin American poverty. My paternal grandparents had sung opera, my Salvadoran mother was a psychologist and a poet, I loved rock and roll and baseball. But during the riots, there was real blood on the streets and desperation in the immigrant neighborhoods, and people were looking for a kind of authenticity they thought I could provide. I represented, as they say, but not without feeling as though I’d entered into something of a devil’s bargain.

I made money quickly (and spent it just as fast). Most of the time I enjoyed the earnest liberal attention and the canapés at the Westside mansions. I spoke on a lot of panels about “public,” or “civic,” journalism (a pre-Web promise to democratize and multiculturalize the media). But a part of me just wanted to write about rock and roll—which I got to do occasionally, but only if it was roc en español.

A few years after the riots I walked away from the gig—though I didn’t get far. I secured a book contract to write about (what else?) immigrants. With the advance money I moved to Mexico City for a couple of years. I think I was trying to flee the American obsession with race, imitating my hero Jimmy Baldwin forsaking New York for Paris. Sure, there was the colonial schism of color in the South, but there was no debate over “illegals” or whether Spanish should be declared the official language. In Mexico I mostly felt at home: I was brown in a sea of brown.

Twenty years later I’m still wrestling with the brown subject, and the city’s media continue to as well. My first job title at the Weekly (“Latino affairs editor”) was clearly a sign of identity politics run amok, of how both white and “of color” essentialized race, which only underscored the problem. There are no designations quite as crude these days, although Pasadena public radio station KPCC did recently post a job description for a co-anchor of a new magazine show “with a focus on the Latino and other ethnic communities/interests/issues,” which sounded very much like an ethnic-specific hire and awfully familiar to this former Latino affairs editor. Shouldn’t the goal be more training for the entire staff to engage the brown-ness of the city rather than heap the responsibility on one brown person? (I am, by the way, an avid listener of the station.)

KPCC isn’t the only media outlet with a brown problem, the persistence of which points to the biggest divide in the city: between immigrants from Latin America and Asia and their descendants, and the rest of “us.” We go to different schools and different churches (or the same ones but at different hours for the English or Spanish or Korean services). We’re all on Facebook, but we’re not all friends. And we most definitely rely on different media. Scan the radio spectrum and listen to L.A. speak in tongues. English-language TV news anchors and reporters look like us—so wonderfully diverse—but not many immigrant families tune in to KABC and listen to the SAP channel translation; they simply go to their cable company’s global menu or the Internet.

But as many boundaries as there are today between the enclaves, countless points of encounter have emerged since the riots as well. We did elect the first mayor of Mexican descent in a century and a half. The white hipster stands behind the brown day laborer in the taco truck line; the taco truck becomes a Kogi taco truck. The mixed-race generation that is coming of age reveals the borders that get crossed in bed, too. Hollywood has slowly but surely begun to reflect these changes. Jimmy Smits became president of the United States on The West Wing long before Obama did in real life. Sofía Vergara simultaneously indulges and sends up stereotype on Modern Family, and Rob Schneider just married into a big brown family.

Yet most of the time the headlines in La Opinión have little in common with those in the Los Angeles Times. If you listen to NPR on KPCC, you’re not going to listen to “El Piolín por la mañana” on KSCA. In and of itself, this difference isn’t necessarily bad. In many ways Los Angeles thrives precisely because it is decentralized, offering the exhilaration of crossing borders. But the divide in media representation—worlds that exist unto themselves even though they are intimately tied to their neighbors—also follows an economic fault line. It is the same kind of divide that led the city to the brink 20 years ago.

On May Day in 1992, I stood on a corner in Pico-Union, the heart of the Central American immigrant community. The air was still acrid with smoke; practically every commercial block in the area had had at least one building looted and torched, and even some residential buildings had been destroyed. In the middle of the devastation there was a bunch of Central American teenagers playing soccer in the street amid dumpsters heaped with charred, soggy debris. They were whooping it up, a sign of life starting to get back to normal. One of them cleared the defenders and took a shot, but the ball went wide and landed in a trash bin. I remember thinking then that there was little hope for L.A. to rise above its contradictions, that there would remain two (or three or four or five) cities, separate and unequal, occasionally colliding with one another.

Today I live in a middle-class neighborhood, Mount Washington, one block away from a working-class, immigrant neighborhood, Highland Park. For the last two nights LAPD helicopters have buzzed overhead after shootings on the other side of the Gold Line tracks where Highland Park begins. The circles the helicopters trace in the air encompass both neighborhoods but do not connect them, though the reverberation—the soundtrack of the city—is felt across the divide between them.

This article is part of ‘Race in L.A.‘